Significance

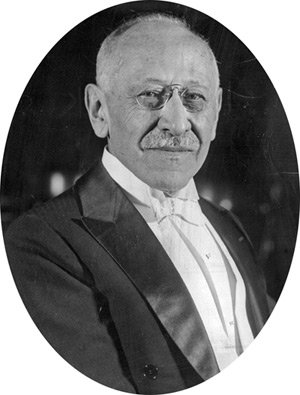

Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932) utilized his fame and fortune for the benefit of humankind through his practice of philanthropy. His fortune was amassed during a career that culminated in his presidency of Sears, Roebuck & Company, and was used to create programs that addressed inequality in the education of Jewish and African-American populations. He is credited with donating more than $65 million to various causes, including creating settlements for Jews in Russia, constructing over 5,000 schools for African-Americans in the South, and building 25 Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) facilities and three Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) facilities to serve African-American communities. His creation of the Julius Rosenwald Fund as a self-expiring entity, ending with his demise, established new criteria for philanthropy.

Biography (from University of Chicago Library Biographical Notes)

Julius Rosenwald was born on August 12, 1862, to Samuel and Augusta Rosenwald, both Jewish immigrants from Germany, in Springfield, Illinois. Rosenwald was educated in the public schools in Springfield, and in 1879 began his business career with Hammerslough Brothers, wholesale clothiers in New York City.

In 1885, Rosenwald came to Chicago, where he joined his cousin Julius Weil to operate Rosenwald & Weil, a retail men’s clothing store. After Sears, Roebuck & Company moved its headquarters to Chicago in 1893, Rosenwald was asked to become a partner in the company. He served Sears, Roebuck successively as vice president (1895-1910), president (1910-1924), and chairman of the board (1924-1932). Under his leadership, Sears developed its lucrative nationwide mail-order business, established savings and profit-sharing plans for employees, and became America’s largest retailer.

Rosenwald married Augusta Nusbaum, of Chicago, on April 8,1890. The couple had five children. Rosenwald died on January 6, 1932.

Rosenwald’s success as a businessman and executive was matched by his many accomplishments as a philanthropist and humanitarian. He played a leading role in many progressive social reform organizations in Chicago, and became the first president of the combined Jewish Charities of Chicago. In 1917, he created the Julius Rosenwald Fund to contribute to the “well-being of mankind.” He supported the work of Booker T. Washington at the Tuskegee Institute and established YMCAs and YWCAs to serve African-American communities in cities across the United States. He funded schools and support buildings for rural African-Americans in the South and contributed $6 million to support Russian Jews settling in southern Russia and Palestine. He also established one of the first urban housing developments on Chicago’s South Side and founded the city’s Museum of Science and Industry.

Rosenwald summarized his philosophy of philanthropy quite simply: “What I want to do is try and cure the things that seem wrong.” He set out on this task with abundant wealth derived from his leadership of Sears, Roebuck, a strong social conscience, and the practical zeal and organizing ability of an eminently successful American businessman.

The things Rosenwald saw as wrong in American society were many and varied, but he focused his prime interest on creating educational facilities for African-Americans, medical care, better government, and Jewish charities and institutions. Rosenwald’s career as a public benefactor extended over three decades and was carried on after his death by the Rosenwald Fund. The termination of the activities of the Rosenwald Fund in 1948 was planned by Rosenwald before he died, since he felt strongly that each generation must accept responsibility for the problems of its own time.

Rosenwald’s papers are housed at the University of Chicago’s Regenstein Library, and record the beginnings and subsequent implementation of the many causes he championed. Rosenwald consistently sought the advice and counsel of many informed public figures. He corresponded with Jane Addams, Booker T. Washington, Mary McDowell, Abraham Flexner, Herbert Hoover, Felix Frankfurter, and many others. But of equal interest and importance were the informative letters of minor figures, who wrote to Rosenwald either to solicit his assistance or to give him guidance.

Concern for justice was the essence of Rosenwald’s great interest in African-Americans. This interest began shortly before the First World War when he met Booker T. Washington and became a trustee of the Tuskegee Institute. While best known for supporting African American education in the rural South, he was also involved with the health and working conditions of those communities through such organizations as the Urban League, the Commission on Interracial Cooperation and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The project that he said gave him greater personal satisfaction than all his other philanthropies was the building of YMCAs.

The record of Rosenwald’s search for an understanding of African-American life and his attempt to apply his resources to solving social problems makes these papers a particularly illuminating source. He explained his emphasis on aid to African-American education quite simply when he said that while white colleges might expect continually growing support, “[so] very few persons are interested in the education of the Negro that I have deemed it wiser to concentrate my efforts in that direction.”

Beyond his aid to the socially marginalized, Rosenwald had a strong sense of the needs of scholarship and learning. The University of Chicago was the recipient of the largest portion of his gifts to higher education, yet he also gave sizable gifts to Harvard University, characteristically including its publication fund and research assistance for Professor Felix Frankfurter. Among his many contributions to the University of Chicago were his early support of the Graduate School of Social Service Administration and his subsidy of several works by Sophonisba P. Breckinridge on public service administration and housing. Learned societies and professional groups, such as the Institute of Pacific Relations, the Council of Foreign Affairs, and the American Association of Museums, were also his beneficiaries.

While many of the social problems to which Rosenwald applied his philanthropy have been addressed by an increasingly complex society, as he knew they would, the principles that guided his giving remain among his most lasting memorials. Rosenwald repeatedly decreed that his giving was intended to attack fundamental causes of human distress rather than to be a mere palliative, and was to be used to support experiments in social improvement which could and should be taken over by the community.

Other public benefactors and trusts have surpassed the amount of money that Julius Rosenwald gave to helping others, but few can match the wisdom and effectiveness with which Rosenwald and the Rosenwald Fund met the problems of their day.

Rosenwald Schools

The Rosenwald School Building Program has been called the “most influential philanthropic force that came to the aid of Negroes at that time.” It began in 1912 and eventually provided seed grants for the construction of 5,357 buildings in 15 states, including schools, shops, and teachers’ houses, which were built by and for African-Americans. The network of new public schools subsequently employed more than 14,000 teachers. At the program’s conclusion in 1932, it had produced 4,977 new schools, 217 teachers’ homes, and 163 shop buildings, constructed at a total cost of $28,408,520. They were to serve 663,615 students in 883 counties of 15 states. Fewer than 15 per cent of the buildings are still standing. The National Trust for Historic Preservation is leading the way to preserve and revitalize the remaining structures, and later this year will hold a conference on the subject entitled “100 Years of Pride, Progress and Preservation: National Rosenwald Schools.

Rosewood Beach Park

Rosewood Beach Park in Highland Park was once part of the Julius Rosenwald estate at Roger Williams Avenue and the lake, which the family owned from 1911 to 1938. Renowned landscape architect Jens Jensen designed the estate grounds. The reflecting pool and surroundings at upper Rosewood Park are all that remain of his work. The house was destroyed by fire a few years after Rosenwald’s death in 1932. The City of Highland Park purchased portions of the original estate in two parts, the first in 1928, and the second in 1945. A private funeral was held for Julius Rosenwald at his private estate on January 7th 1932. He is buried at Chicago’s Rosehill Cemetery.

_________________________

Bibliography and Internet Sources

Ascoli, Peter. Julius Rosenwald: The Man Who Built Sears, Roebuck and Advanced the Cause of Black Education in the American South. Indiana University Press. 2006.

Embree, Edwin R. and Julia Waxman. Investment in People: The Story of the Julius Rosenwald Fund. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishing, 1949.

Jarrette, Alfred Q. Julius Rosenwald: Son of a Jewish Immigrant, a Builder of Sears, Roebuck and Company, Benefactor of Mankind. Greenville: Southeastern University Press, 1979.

Mann, Louis L. “Julius Rosenwald.” In Dictionary of American Biography, edited by Dumas Malone. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1935.

National Trust for Historic Preservation. 100 Years of Pride, Progress and Preservation: National Rosenwald Schools Conference. June 2012. www.preservationnation.org/travel-and-sites/sites/southern-region/rosenwald-schools/

Roberts, Alicia S. “Julius Rosenwald.” Paper for Philanthropic Studies course taught at the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University. Indiana. www.learningtogive.org/papers/paper121.html.

Rosenwald, Julius. “The Burden of Wealth,” The Saturday Evening Post (5 Jan 1929): 12-13, 136.

University of Chicago Library. Julius Rosenwald Papers 1905-1963. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Werner, M.R. Julius Rosenwald: The Life of a Practical Humanitarian. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishing, 1939.